|

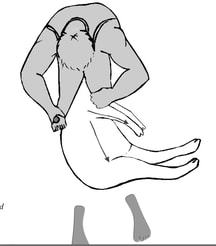

One unexpected trip to Ohio and one spring break later, I'm hopeful that we have finally arrived at the point where - following this next absence - I will not be away from the shop every third week for the rest of the year. I'm anxious to get back into my normal routine and not worrying about whether or not I remembered to change the answering machine, stop shipments, and the fifty other tiny tasks that have to happen when I'm away from the shop for an extended period of time. But I do have one more week-long absence planned from April 22 - 27 so that I can attend the Washington State Wool Producers' Shearing School in Moses Lake, WA. "Shearing?" you might be saying. "But... you're a YARN shop, not a farm - you've said you don't even have sheep! Why would you do this?" Excellent question! Over the last couple of years, I've fielded a ton of questions from a variety of community members about where they can find shearers - during the lockdown phase of the pandemic, it seems that quite a few folks decided to add sheep to their properties. However, if you're not dialed in to the local 4H or FFA chapters - or if you're not involved in a homesteading or small farming group - you may not know how to go about getting connected with a shearer. And there aren't a ton of shearers available, either. The folks who are available to hire for shearing are usually booked up in advance of the lambing season, and they usually won't travel to individual farms or homes for small-scale shearing - you bring the animals to a central location and have them shorn there for efficiency's sake, then take them home. So you make do with whoever happens to have the equipment - whether or not they have training - and you get the wool hacked off your poor animal, and it sits in a bag because you feel like it's too good to waste... but you have no idea what to do next. So you call the yarn shop. If you ask a certain yarn shop owner about shearing enough, she's going to look into what it requires... and eventually she'll apply, because conversations like the ones outlined above are happening more and more often. AND she's talked with milling colleagues from various cottage mills in the area to see what their take is, and she discovers that THEY are also having these conversations but maybe don't know how to get word out to farmers and shepherds about their processing services. Said yarn shop owner realizes she's in a unique position to bridge that gap, applies for shearing school, and gets into the 2024 class. So. All that to say that I'm going to shearing school in a week, and it's expensive. How's that, you might ask?

Add to that the fact that the shop will be closed for another full week - and that there's no way I can recoup my investment in a single year just by picking up shearing jobs - and it becomes clear that I'm going to need to ask for help in a few different ways. How can you get involved with this effort?

We take this ask VERY seriously. We've always been a full-service yarn shop, but being able to get out in the community to provide responsible, informed shearing services to our local fibershed takes it to a different level. Many of you reading this have shared how important the shop is to you and how important it is to you to support local agriculture and local businesses. Making a purchase or donation, sharing this post or our related social media posts, or even just sharing by word of mouth that there will soon be someone available to help with small-scale shearing are all ways that you can help the shop keep going and help us support colleagues working in various aspects of the local fiber industry.

2 Comments

Worsted-weight yarn - also known as #4 yarn - is tied with fingering-weight yarn for the most popular yarn weight in our shop. It’s where most beginners start, and it’s got a huge range of options available.

But what does “worsted” even mean? What did it ever do to get so harshly judged? Read on and find out! According to the Craft Yarn Council guidelines, a worsted-weight yarn might also be known as “afghan yarn” or “aran-weight yarn.” (While aran-weight is generally in this category, it’s actually not exactly the same as a worsted-weight; it’s slightly thicker, but not enough to qualify as a bulky-weight yarn.) In crochet, you can expect a worsted-weight yarn to get you about 11-14 single crochet stitches in 10 cm / 4”; in knitting, it’ll get you 16-20 stitches in stockinette in 10 cm / 4”. The average hank of worsted-weight yarn runs between approximately 146-210 meters / 160-230 yards in 100 grams / 3.5 ounces. In the shop, we have a lot of options for you in worsted-weight yarn: Berroco Vintage, Malabrigo Ríos, Noro Haunui, and Ella Rae Cozy Alpaca Worsted, just to name a few. So where does the term "worsted" come from, anyway? This one is fairly easy to trace. Back in the Middle Ages, a village near Norfolk became a textile center known for two things: long-fleeced sheep and a fabric woven from the strong, smooth, dense yarn that was spun from those sheeps’ fleece. Various sources agree that this village was known for the quality and output of its textile goods for over 600 years. That village’s name? Worstead. How did it come to apply to a specific yarn weight? That’s a little harder to suss out. It seems to come from the fact that the fiber and yarn produced in Worstead were composed of smooth, denser wool with a longer fiber length. After the wool industry was well-established in Worstead, the type of yarn the village produced became generally known as “Worstead yarn”... and over the years, the spelling changed to “worsted.” But wait, you might ask. If there’s “Worstead / worsted” yarn… that implies that there’s a different term for a different type of yarn, then? And the answer is yes - you’re absolutely correct about that. Without going too deep into the weeds on this, commercial yarn comes in many different forms and structures, but the way it’s spun generally falls into one of two categories: worsted-spun and woolen-spun. Worsted-spun yarns are like Berroco Vintage or Malabrigo Ríos; I refer to them as the brownies of the yarn world. They’re smooth, dense, and pretty easy to find. Woolen-spun yarns are like Harrisville Highland or Brooklyn Tweed Shelter, and I refer to them as the meringues of the yarn world. They’re lightweight, lofty, and somewhat more difficult to find these days. (You can get more information and see the difference between these two types of yarn in an article by Jillian Moreno over at Modern Daily Knitting if you want to learn more.) Taking all that into consideration, then, it seems like the type of yarn originally produced in Worstead gave its name first to a spinning technique and lightweight garment fabric, and that name then got applied over time to describe a specific size of yarn. It’s odd to me that it wasn’t pulled into use for the smaller size of yarn you’d typically use for durably woven clothing fabric, but maybe it just became good enough as a descriptive word, and that was that. Want to read more about all the different uses of the term “worsted”? Read more about it over on HandwovenMagazine.com in an article by Susan E. Hornton. Next week, we’ll wrap up this series of blog posts with a quick look at bulky and jumbo yarns, then take a break for a couple of weeks. IDK, what's DK?

Sport-weight and DK-weight yarn are the most-confused yarn weights in the shop, and there’s a lot of overlap between them. You sometimes even see that the yarn company has labeled the yarn one way and I’ve chosen to shelve it with a different category of yarn (Malabrigo Arroyo, I’m looking at you in particular). According to the Craft Yarn Council, DK-weight yarn is a yarn that works up at 12-17 single crochet stitches per 10 cm / 4” or 21-24 stitches in stockinette per 10 cm / 4”. It is sometimes referred to as “light worsted” as well. An average hank of DK-weight yarn is 229 - 297 meters per 100 grams, or 250-325 yards per 3.5 ounces. In the shop, our DK-weight selection includes Berroco Spree, Berroco Vintage DK, Ella Rae Eco Tweed, and West Yorkshire Spinners ColourLab DK. That’s all well and good, you might say. But let’s cut to the chase - what does “DK” stand for? DK is an abbreviation for “double knitting.” You may have run across this in the context of a knitting technique that produces a double-thick fabric (sometimes with knitted-in 2-color designs that are reversible and switch colors from one side to the other). In the case of the term applied to yarn weights, however, it has more to do with the physical structure of the yarn. One of our most popular sock yarns (yes, true sock yarns) is West Yorkshire Spinners’ Signature 4-Ply. If you pick this yarn apart into its structural components, there are indeed 4 singles plied together to make one yarn. In Great Britain and many of the former and current countries of the British Commonwealth, you’ll often see fingering-weight yarn simply referred to as “4-ply.” DK-weight yarn is now often referred to as “8-ply” in those same areas… which is double the plies you find in the 4-ply yarn. Fingering-weight held double is thus - (4 plies x 2 strands) = 8-ply. When you hold it double to knit it at a larger gauge… you get “doubled knitting [or crocheting] yarn.” And if you’ve ever held fingering-weight double to substitute in for another weight of yarn, you’ll often find (depending on the original skein) that it’s about the same as a heavy DK-weight yarn. And by and large, that seems to be about the entire story. Sidebar - crocheters in the audience are likely crying foul that this shows the bias inherent in the system towards knitters. And you’re not wrong. However, it’s likely that this was the result of where crochet in Europe and North America was focused in the 19th- and early 20th-centuries: trims and laces. These pieces were often worked in fine thread, not larger yarns - larger yarns were generally reserved for knitting, or sometimes weaving. This tendency to distinguish between which yarns can be used for which crafts might also be reflected in any experience where you’ve heard a crocheter ask if the yarns in a given store can be used for crochet. In today’s yarn world, yes, of course! But crocheting with materials thicker than crochet thread - at least in the American and European practice of crochet - is a relatively recent development. Can you imagine knitted gym shorts? (Or, what does “sport-weight” mean?)

We’re going to move up the yarn weight scale a notch at a time for the duration of this series, and today we arrive at the “sport-weight” designation. The Craft Yarn Council defines sport-weight yarn as a yarn that achieves a crocheted gauge of 16-20 single crochet in 10 cm / 4” or a stockinette gauge of 23-26 stitches in 10 cm / 4”. In comparison to the fingering-weight yarns we looked at last week, you can see that this is a pretty limited gauge range - that will be the case for most yarn weights moving forward. An average hank of sport-weight yarn is going to come in somewhere between 297 - 348 meters per 100 grams, or 325 - 380 yards per 3.5 ounces. Examples of sport-weight yarns that we carry in our shop include Kelbourne Woolens Mojave, Juniper Moon Farms Patagonia, and Malabrigo Arroyo. Given American culture’s semi-obsession with sports and athletics and fitness, it’s a natural question to wonder what connection this type of yarn has with that world. Preppy tennis sweaters of a certain era or vintage bathing suits may be the only thing you can conjure up in your mind that would have perhaps been crocheted or knitted garments, but would that really have been enough to name an entire yarn category after sports? Short answer: the language and culture have shifted, and the popular meaning of “sport-weight” is now very different from what the term was originally coined to mean. There are all sorts of origin stories for the term “sportswear” depending on which sources you consult, but in general, it seems like the best description is that sportswear started out as collections of mix-and-match separates that were derived from types of actual clothing pieces worn by athletes. These separates were more relaxed than the typical silhouettes of clothing of the very early 20th century, less strictly relegated to specific activities or times of day, and - for women in particular - allowed them to dress themselves fashionably and easily without requiring the assistance of a maid. I found particularly interesting examples in an article attributed to Patricia Campbell Warner on LoveToKnow.com, titled simply “Sportswear.” Think of trousers, button-up shirts, cardigans, tunics, and turtleneck shirts. These separates were also made of materials that were easier to care for than more formal outfits, such as cotton, wool, and linen. Over the past few decades, the term “sportswear” has become more specifically linked to clothing you wear while participating in sports - in the US, we might call it “athleticwear,” or even “athleisure-wear” if you’re running errands in the same clothes you would wear to a yoga class or strength-training session. What used to be “sportswear” is now probably better called “business casual.” So what does this all have to do with yarn? Finer-gauge crocheted and knitted clothing is often perceived as dressier or appropriate for a wider range of settings - think of super-bulky pullover sweaters versus twin-set cardigans and shells. So the yarn that we now call “sport-weight” would originally have been used to make pieces of clothing that would have been appropriate to both pay a social call to an acquaintance and attend less rigidly formal social events, but not appropriate in an important business meeting or a high-society gathering. As a note, another name for this yarn weight is “baby yarn.” Again, “baby yarn” can be used to describe a number of characteristics of yarn but is normally used today to describe yarn that is both soft and easily washable. The use of the term “baby yarn” specifically tied with this size of yarn most likely has more to do with the development of easy-care yarns in acrylic and other synthetic materials in the period following World War II. As sportswear moved from natural materials to newly-developed synthetics, the same marketing push that encouraged homemakers to purchase clothing and home linens that could simply be thrown in a washing machine at any time also moved into the yarn market. Why risk making an heirloom sweater out of wool that could accidentally be felted or attacked by moths when you could pick up a skein of yarn specifically formulated to go in the washer any time the baby threw up on it or crawled through dirt? It’s fascinating to see what historical trends continue to play out in our use of language - stay tuned, as our next two installments will also have a lot to do with this idea! Nope. Well, not necessarily.

Let’s back it up a step, though. “Fingering-weight.” Where does that term even come from? The most-often cited etymology is from the French phrase “fin graine,” meaning “fine-grained.” As a French speaker… well… that gets some serious side-eye from me. The word order is wrong, and it doesn’t appear that “graine” is a word that has applied to wool or yarn*. Additionally, as Norman at the Nimble Needles blog points out, yarns in Europe are sold by the size of needle you would use with them and not by general category. Norman did some excellent detective work and tracked down what he believes to be the origin of the term - in the Scottish National Dictionary, a type of woolen cloth is labeled “fingering,” which the dictionary proposes comes from a spinning technique that, by that time, had been lost in terms of its relationship to the creation of the yarn used in the fabric. (Seriously. Go read Norman’s post. It’s FASCINATING.) Fingering-weight yarn, according to the Craft Yarn Council standards, averages a single crochet gauge of 21-32 stitches in 10 cm / 4” and a stockinette gauge of 27-32 stitches in 10 cm / 4”. That’s an incredibly wide range (especially for crochet). The “put-up” - how many yards there are in a standard skein or hank - can range from 366 meters / 400 yards in 100 grams to 425 meters / 465 yards in 100 grams. That’s a 14% difference in yarn thickness between the ends of the range! Why, for so many people, does “fingering-weight” then automatically equal “sock yarn”? Smaller stitches tend to both feel better on the foot and wear better over time in high-friction contexts - so it makes sense to make socks out of finer yarn. And why is THAT, you might ask? The soles of our feet are incredibly sensitive. Think of how fine some of the grit is that you find in your shoe after a walk on the beach, and how disproportionately annoying it is to figure out what’s bugging you in your shoe before you sit down and tap it on a bench or a curb.. The purl bumps on the inside of a sock are more uneven than the knit side, so if you have larger yarn in a sock, everything about those purl bumps is going to feel unusually irritating. (There is a solution to this - called a “princess sole” - which has you purl the stitches on the sole of the sock so that the smooth knit-stitch side is directly against your foot.) Using large yarn means your stitches are larger, and more of each stitch is going to be exposed to abrasion and wear away more quickly than the small stitches. So if fingering-weight yarn isn’t automatically sock yarn, then what gives? What IS sock yarn? That’s an excellent question and one that will kind of depend on who you ask. At the shop, I maintain that sock yarn has two very important characteristics - 1, it’s tightly plied. 2, it contains some sort of fiber that is going to help combat destructive abrasion. Tightly plied yarn is going to expose less of each strand of the yarn (called a single when we’re talking about yarn construction), and it’s going to be springy - and therefore able to stretch and give in response to the movement of your foot. The second fiber is going to strengthen the yarn - it’s often nylon, but sometimes silk or mohair are used instead. There are several yarns on the market in DK-weight and worsted-weight that are specifically pitched as sock yarns because they meet these two criteria, and I agree with that classification. The takeaway - there are several different positions on this, but I’m going to come down on the side of saying that it’s only sock yarn if it meets specific conditions that will help it resist abrasion and stretch to help with the negative ease that most socks require. Fingering weight can be all over the place in terms of fiber content and yarn construction, but if it doesn’t have a strengthening agent or tight spin, I’m not going to recommend it for durable socks - and therefore it’s not a true sock yarn. *I need to absolutely confirm this with my big French dictionary, but it is currently behind about 35 kg / 80 lbs of boxes in our home library - the online version of this same dictionary has definitions from the 17th century, which do not include fabric / fiber grain among its definitions, either. One of the most frequent requests we get for assistance in our shop is to help people find the right yarn for their project. Either the pattern calls for a very specific yarn and doesn’t give information on equivalents, or the pattern calls for a specific “weight”of yarn but assumes the crafter knows exactly what to ask for. If you’ve ever seen a pattern that calls for “fingering-weight yarn,” or “baby yarn,” or “a #2 yarn”, you’ve dealt with yarn weight.

This is a vast and complex topic, but let’s break it down into some basic bullet points this week. 1 - “Yarn weight” is kind of* another way of saying “yarn size.” (*it’s complicated) When you search for yarn in a certain weight, you’re looking for a yarn that, due to its general ratio of yards to ounces (or meters to grams), is likely to act the way you expect it to in a given pattern. This is a bit of an overgeneralization, as the way a yarn is spun can cause it to behave like other yarns in a given “weight class” but look like a very different yarn weight on the shelf. 2 - There are at least 3 ways that people assign a weight to yarns. You’ll see yarn weight assigned solely based on the ratio of yards to ounces / meters to grams, or by stitches per inch, or by wraps per inch. The first two methods are the most common; wraps per inch (or WPI) tend to be more used by weavers and spinners. 3 - Not everyone agrees on the “correct” way to assign a yarn weight classification. The more information you have on a given yarn, the more of an understanding you have on how that yarn is likely to behave in a given pattern, or on a given hook or needle size. Most of our commercial yarns at the shop have the ratio on their labels as well as the stitches per inch measurement. In the shop, I tend to rely pretty heavily on the ratio method to assign yarns their spot in the shop since the shop is laid out in yarn-weight order; however, I also take into account technical knowledge about how some of our yarn options are spun when I’m making that decision. (More about that in a later post!) When I’m working with customers to decide on which yarn is right for their pattern, the ratio method gives me a ballpark idea of where to look for a good match; the washed, blocked swatch will give us the final answer with the most accuracy. There’s a group called the Craft Yarn Council that has a chart with all kinds of information on how yarns in the same “weight class” can be measured - you can get it for free at craftyarncouncil.com. 4 - Crocheters and knitters often use different scales to describe the same yarns. Crocheters in the US tend to use a numerical scale that runs from 0-7 to classify yarns. Knitters in the US tend to use a word-based scale (cobweb, lace, fingering, sport/baby, DK, worsted, aran, bulky, super-bulky, jumbo) to classify yarns. They can be used interchangeably to describe the exact same yarns, just in different terms. 5 - Even if a yarn is labeled the same weight as what you need for a pattern, not all yarns in the same yarn weight are equal! Yarn weight categories cover a LOT of ground. Just because something is classified as a “worsted-weight” or #4 yarn doesn’t mean it will knit up exactly like the #4 / worsted-weight yarn that the designer used - especially if the designer didn’t specify which yarn they used! A yarn that has alpaca content and 175 yards per 100 grams isn’t generally going to behave the same way as a mostly acrylic yarn that has 230 yards per 100 grams, even if they’re both called worsted-weight yarns by the yarn company or the yarn shop. This is where gauge swatches come into play. Pattern yarn recommendations are ultimately guidelines. Even if you use exactly the same yarn and hook/needle size as the designer, you might not be able to get the same gauge they published in the pattern because you crochet/knit more loosely or tightly than they do. So there you go - watch this space over the next few weeks for more posts about specific aspects of yarn weight. We'll post a new article each Tuesday and let you know on our social media feeds (Instagram, Facebook, and Threads). It's true! Whether you want to start planning for the winter holidays, graduation, a birthday, a promotion, an anniversary, retirement, or any other special occasion, you can create a wish list that stays on file at the shop.

How do I start a wish list? Our register software is amazing - it runs your customer cards, your purchase history, payment plans for equipment... but it also has the capacity to keep a wish list on file for you. You can put specific items from the shop on your list, or you can ask us to add something that we can special-order for you. Just let us know when you come in, send us an email, or give us a call and we'll add items of your choice to your list. It could be yarn... interchangeable hooks or needles... a loom... a drop spindle... basically anything that you'd love to have show up! As items get purchased from your list, they will disappear so nothing will get bought in duplicate. How do I access it? Get in touch with us and we'll be happy to print or email you a copy. How can people make purchases from my wish list? Have them get in touch with us! What if there's an expensive thing on the list that people want to pool money for? We can absolutely set up a multi-person payment option for anything on your list. All they have to do is ask. (Please note that we won't ship or release the item for pick-up until it is entirely paid for; special orders need to be paid in full before we are able to order them.) Do I have to pick things up? Or does the person ordering have to pick things up? Nope! We're happy to accommodate those options, of course, but we can also ship items, call the recipient on your behalf and let them know they have a surprise waiting, or just about anything else. Can I surprise someone? Absolutely. Just let us know when you make the order and we'll conspire with you for the best possible surprise in the format that works best for you and them. Just about a year ago, Nancy Bates released her blockbuster pattern book, Knitting the National Parks. The book includes one hat pattern for each of the 63 national parks in the United States, and the response has been absolutely amazing. People knit hats for friends and family's favorite parks... or knit hats in anticipation of being able to wear them on their trip to those parks... or just to have some fun, eye-catching headgear for cool weather! Our shop community is full of travelers, hikers, and nature enthusiasts of all stripes, so of course this book has been a hit for us, too. As of last week, we had had about 18 different hats brought to the shop to show them off - it's been awesome to see what people have been drawn to! (Far and away, Mount Rainier is the most popular hat as of this writing; North Cascades, Crater Lake, and Denali have been close behind.) As you may know, I try to post customer work on as many Fridays as possible over on our Instagram account - the hats have featured prominently for much the past year. When Kris brought in her Shenandoah hat a few weeks ago, I grabbed a photo on the porch and then saved it to post last week. I wondered idly in the caption if perhaps - between now and the first day of spring in 2024 - the shop community could manage to complete at least 1 example of all 63 hats in the book. And then this happened. We are nothing if not up for a good challenge - especially with the reward of an amazing designer coming to visit us - and so the shop community leapt into action.

We're officially inviting all shop community members to participate in The Great National Parks Hat Challenge! Between now and March 18, 2024, pick any hat (or hats!) that you want to make, let us know which ones you're working on, and we'll get you on our spreadsheet. If you're looking to help us fill holes in the spreadsheet, you can see it here - with some help from generous shop community member JH, we even have difficulty ratings for each hat if you're having trouble figuring out which one might be a good starting point for you. Once you've finished your hat, please submit it through the Google Form so we can keep tabs on how close we are to reaching our goal! Even if you see that the hat you want to make is already being worked on or completed, we want you to join us in this group effort - no one has exclusive dibs on any of the hats, no one gets a prize for completing the most, and we're not requiring that yarn be purchased through the shop. Of course that would be lovely, but we also know that everyone's budgets are running tighter than normal this year - use as much as you can from your stash, find a stash buddy to share partial skeins or split the cost of a single skein you can use in multiple hats, but most importantly... HAVE FUN! Nancy Bates is ready to do this. Let's give her the chance to experience the unique welcome and community that you can only find at Stilly River Yarns. One of the most common things we get asked is about how yarn is packaged - is there any difference between a ball and a cake of yarn? Is a hank the same thing as a skein? (Skeen? Skayne?) Where do "yarn donuts" come into the mix? These are all different ways of talking about what is called the yarn's physical "put-up." The most common commercial “put-ups” by physical presentation are hanks, skeins, and donuts. Here's what they look like in the wild: Hanks are the twisted presentation that you see in Berroco Vintage, Noro Sonata (shown at left above), and Malabrigo Rios, just to name a few examples. To avoid absolute madness, hanks need to be wound - either by hand into a ball or using a ball-winder to make a cake.

Skeins are the football- or cylinder-shaped presentations that you see for yarns like West Yorkshire Spinners Signature 4-Ply (shown in the middle above), Red Heart Super Saver, and Berroco Remix Light. These have already been wound at the mill in a configuration where you can pull the yarn from the center without requiring winding at the shop. Donuts are… well, shaped like donuts. In our shop, you can find Berroco Coco (shown above at right), Gedifra Metal Tweed, and Gedifra Soffio/Soffio Colore. You can easily pull from the outside or inside of the ball, but they are hollow and usually have a label that goes through the middle of the ball. (They also shed layers of yarn like crazy and get “drippy” - they’re our least favorite put-up.) A very few yarns come pre-wound into center-pull cakes or balls, but those are less prevalent in the American market; Juniper Moon Farms Cumulus Rainbow and yarns in the Zauberball family are examples of these. So why do companies choose to ship their yarns in all these different formats?

Okay, so how *do* you pronounce the "skein" word? Excellent question - it's pronounced "skayne," with a long-a sound in the middle. What about yarn cakes and yarn balls? These are generally terms used to describe how yarn is wound from a different form (usually a hank) to prepare it for use by crafters. A cake (at left below) is generally formed by winding yarn around some kind of cylinder, whether it be a mechanical ball-winder, a nostepinne, or a toilet paper tube; a yarn ball (at right below) can be created just by winding a yarn around your fingers, folding it into a nucleus, and then winding the yarn in different directions around the nucleus. I wish we weren't still in such limited operation... alas, we are hitting our third peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, and we're still unable to welcome visitors and social times as we would normally be enjoying doing at the busy intersection of cooler weather and the winter holiday season.

That being said, Small Business Saturday is still happening this year, and we're extending it for an entire week so that we can observe all the necessary public health guidelines to keep our shop staff, families, and community safe. Our Week of Small Business Saturday will run from Saturday, November 28 through Saturday, December 5... and that means all our deals and special activities will run for the entire week, too! Here's what you can plan on:

And as always, thank you for supporting Stilly River Yarns (and all of your other favorite local small, independent businesses). It's been a heck of a year, but we're grateful to still be able to be here serving you. -Lindsey |

AuthorLindsey Spoor is the owner of Stilly River Yarns in Stanwood, WA. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

Reach out! |

Come visit us at our brick-and-mortar shop in Stanwood!

NEW LOCATION STARTING JULY 16, 2024:

7104 265th St. NW Suite 120 Stanwood, WA 98292 Shop phone: (360) 631-5801 Email: [email protected] Text: (515) 833-0689 |

|

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

Stilly River Yarns LLC

Copyright © 2024

Copyright © 2024

RSS Feed

RSS Feed